ENGLISH DRINKING VESSELS:

Black

Jacks, Bottells and Other Items

(Part 1: Black Jacks)

by Modar Neznanich

I. Introduction

The existence and history of leather drinking

vessels has been firmly established. An entire book was written on the subject,

entitled Black Jacks and Leather Bottells. There are also several leather

drinking vessels that have survive from the Middle Ages. Many of these extant

pieces are located in the Museum of Leathercraft outside London, England. Other

extant pieces are on display in some of the pubs throughout England, and four

are located at Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. (I had the good fortune

to examine these last four, first hand, and was allowed to speak to several

audiences on their construction.)

II. Definition of

Terms

To make sure that it is easier to understand

the terminology used, the following definitions have been

provided.

Jack -- Also called a blackjack or a black jack. A

tankard made of leather (usually tar-coated) for holding beer or ale. The jack

received its name from its distinctive shape. The archers and guardsmen of the

time wore a gambeson-style jacket of defense that was a sleeveless coat which

came straight down the sides and flared out at the bottom, when it got to the

hips. This body protection was called a jack. Because the drinking vessel had

the same silhouette, it also became known as a jack. Over time it became known

as the black jack, because the majority of them were coated inside with a

black pitch or pine tar resin to make them waterproof. Many times erroneously

called a bottle of leather.

Bombard -- A giant-sized jack, usually with a holding

capacity of 1 to 5 gallons. Named originally after the late medieval cannon

used to hurl large stones, because both had huge openings.

Bottell -- Also called botel, botil, botill and bouteille.

The modern word of bottle derives from it. A rigid or semi-rigid container for

liquids, having a comparatively narrow neck or mouth and usually no

handle.

Can -- A cylindrical drinking vessel with straight

sides, similar to modern coffee mugs. Some had handles, some did not. A few

even had removable tops, but most had an open top.

Pot -- A generic term for any type of drinking vessel

whether made of leather, wood or metal. It is from this term that the word

"potable" (meaning suitable for drinking) comes.

Tankard -- A tall one-handled drinking

vessel.

III. Why Was Leather

Used?

The development of drinking vessels made of

leather arose from the fact that during the Middles Ages there was no glass

production and little pottery production in England. Records show that pottery

vessels (made of clay) were not as common as many believe. While the records

show there were quite a few potters in England during this time, they were

makers of metal pots. Records had a special term for those who produced vessels

from clay. They were called Erthpotters, and there were very few of them. Almost

all the earthenware vessels produced during the Middle Ages, in England, were

either large pitchers for liquids or large "urns" for preserving and storing

goods. All other glass and pottery was imported from other countries, most

notably France. (It was also noted in the records of the time that the "native"

clay vessels were inferior to the imported clay pottery, and hence less

desirable to own due to the fact that they easily broke.) The cost of importing

glass and pottery products, particularly due to high tariffs, made it

impractical for the common man to purchase them. Reasonably, people turned to

other available resources to produce needed items out of. One of the resources

used was wood. Crockware (composed mainly of dishes, plates, saucers, platters,

trenchers, some utensils and a few cups) were produced from wood. Metal was used

mainly for utensils, although there are some examples of it being used to make

plates and cups. The other plentiful resource available at the time was leather,

and most drinking vessels were made out of this.

Besides being plentiful and cheap at the

time, leather had other advantages. It could be easily made into various sizes

and shapes to fit one's need. Once coated with pitch (or other linings such as

tallow made from beef/mutton fat, pine tar resin or wax), leather remained

extremely waterproof, did not warp out of sealable shape like wood could, and if

dropped, it did not break like expensive glass and pottery.

This process of lined leather is noted by

John W. Waterer on page 92 of the book, Leather Craftsmanship, "Some of

the more spectacular of moulded articles were the drinking vessels called 'black

jacks' and their relatives, the great jugs or 'bombards'; were lined with pitch

or resin [such as wax, beef or mutton fat tallow or pine tar] to prevent liquor

from soaking into the leather and softening it."

IV. Timeline of Leather

Vessels

In an attempt to allow visualization of when

leather vessels were in use, the following rudimentary timeline has been

provided.

A rude cup of hide, dating back to the

Neolithic period, was exhumed, along with other remains, in West Smithfield,

England.

A Saxon barrow (funeral mound) located

eight miles from Buxton, England had inside the remains of a silver-edged

leathern cup. It was three inches in diameter at the mouth. It had

ornamentation of wheel shapes and crosses.

The earliest known written record

concerning leather drinking vessels in England was in the Colloquy of

Archbishop Alfric. Written in the Tenth Century, it speaks of the wares

produced by leathercrafters which included bottles, flasks and

bougets.

From Guildhall records of the

leathercrafters, we know that leather vessels were in great production by the

1300s, and that the Botellers (makers of bottles and other leather drinking

vessels) were forming their own guild, separate from the other

leathercrafters. The records show they had exclusive right to make all leather

drinking vessels.

In the 15th century, the Botelmakers Guild

and the Horners Guild combined into one guild. Perhaps showing the beginning

of a decline in the use of leather vessels.

V. Historical

Sidenotes

It is theorized that the concept of a

leather sap used to knock people unconscious, being called a blackjack, arose

from bar fights where the black jack drinking vessels were used as weapons to

fight with. As Oliver Baker states on page 99 of Black Jacks and Leather

Bottells,"In Heywood's 'King Edward IV' (1600), Sir Thomas Sellinger says,

'Now by this light! Were I but near the Knave with a black jack, I would beat

out his brains.'"

The jack was well loved by its users. So

much so that there are several songs written in period about it. One such song

recorded by Oliver Baker on page 102 of Black Jacks and Leather

Bottells goes:

"He that drinks in a Jack looks as fierce

as a Spark,

That were just ready cockt to shoot at a Mark;

When the

other thing up to the Mouth it goes,

Makes a Man look with a great Bottle

Nose:

All wise men conclude that a Jack New or Old,

Tho' beginning to

leak is, however, worth Gold;

For when a poor man on the way doth trudge

it,

His worn-out Jack serves him for a Budget;

And I wish his Heirs may

never lack Sack

That first contrived the Leather Black

Jack."

VI. Production of a

Jack

A short synopsis of the general procedure

consists of cutting out the three leather pieces needed, sewing the shell piece

and plug piece together, soaking the shell piece in water, forming the shell

over a mould, allowing the shell to dry, removing the shell from the mould,

sewing in the bottom piece, lining the insides, dyeing/decorating the exterior

and sealing the exterior.

Basic Tools

Needed:

1. Dye Daubers

2. Burnisher

3. Pressure

Clamps

4. Groover

5. Leather Knife

6. Mould

7. Needles

8.

Paper

9. Pattern

10. Pencil

11. Sandpaper

12. Spacing Wheel

13.

Stabbing Awl

Optional Tools Need (for

decorating)

1. Modeling Tool

2. Paint Brushes

3.

Stipler

Materials

Needed

1. Leather, 9/10 weight oak-tanned

2.

Leather cement

3. Thread, 6 strand flax (linen) waxed with beeswax

4.

Coating/Resin/Pitch

5. Wax Paper

6. Leather dye

7. Paint (Optional -

for decorating)

8. Lacquer

Step-By-Step

Instructions

1. Determine the shape and size desired.

Most jacks in period were of quart-size, and shaped like the jack

"standardized" by Master Trobere Oakseed from the vessels illustrated in the

book Black Jacks and Leather Bottells by Oliver Baker. It is this

style of jack that will be discussed here. Variations in shape and size will

not affect the steps needed to produce a jack.

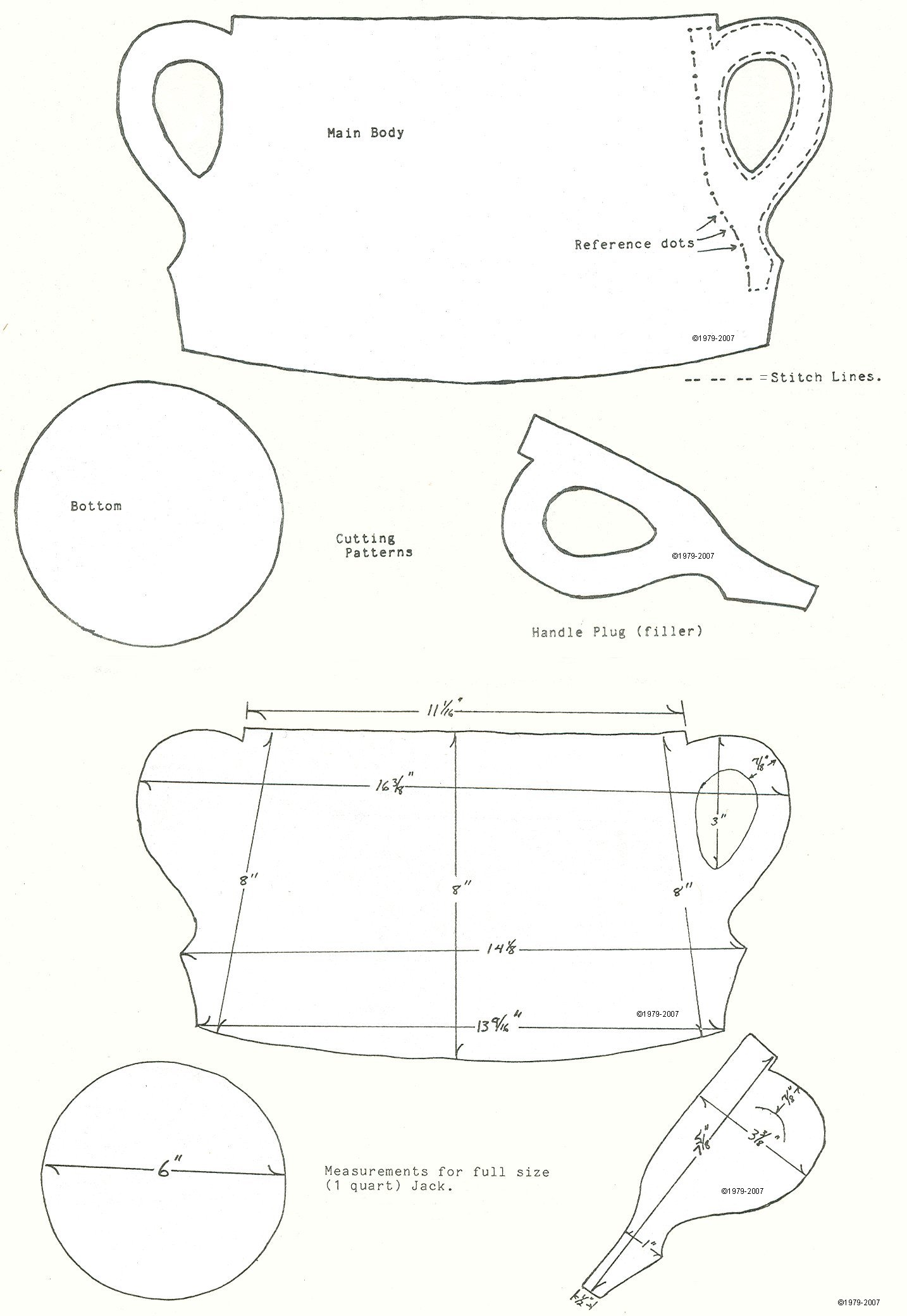

{Jack Pattern

learned from Master Trobere Oakseed}

[Click picture, save then print out to get larger view of

pattern]

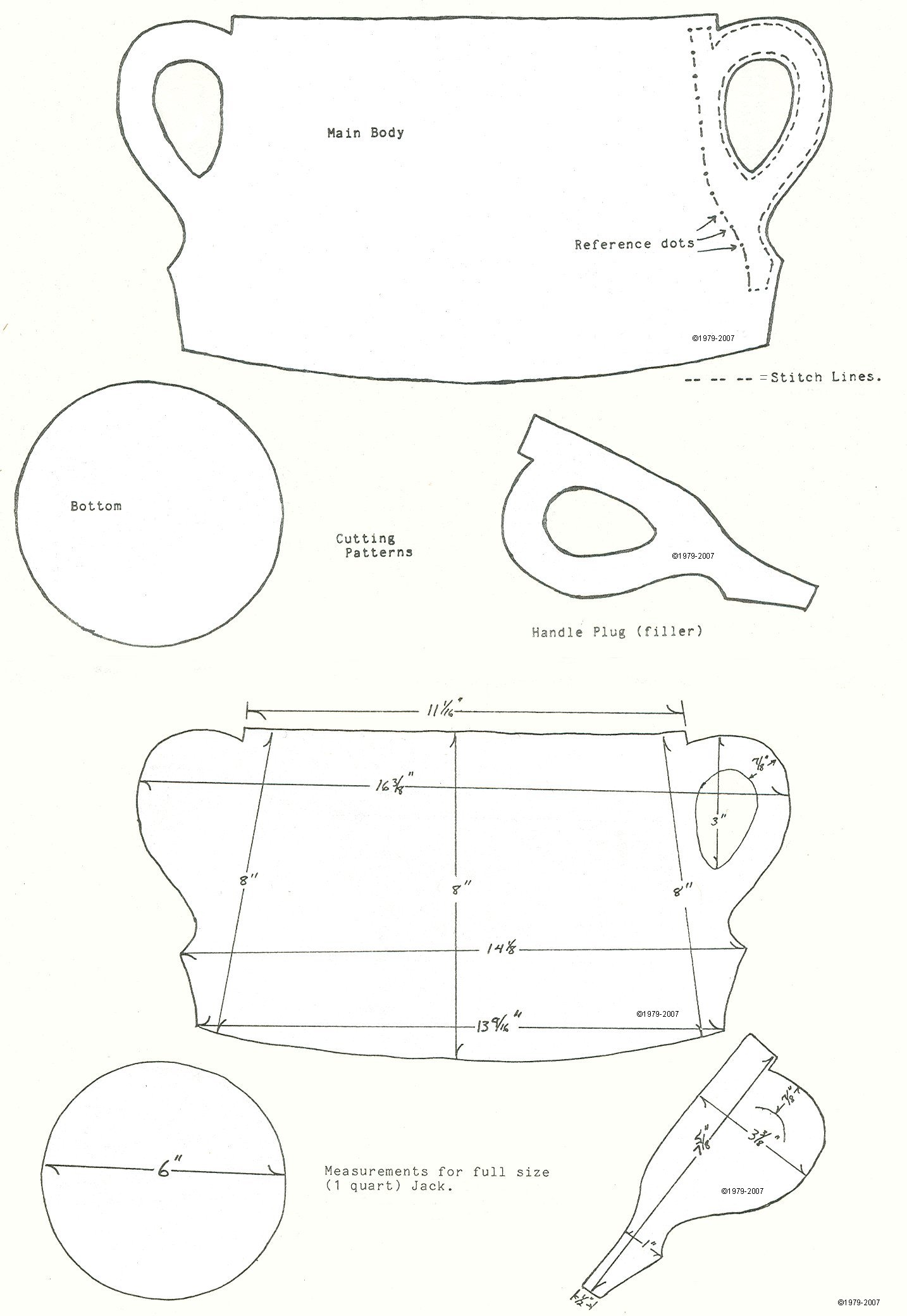

2. Once the design/shape is determined, a

form or mould matching the shape that the jack will have, has to be made.

Normally this mould is produced out of wood. This involves either forming

one on a lathe or having one made for you. Attached is a drawing with the

shape and dimensions that the mould needs to have in order to produce a jack

in the "standardized" style being discussed. It is suggested that oak or

rock maple be used to make the mould as this stands up to use the best. How

the mould is used is that the leather shell is soaked, then stretched over

the mould and allowed to dry. Once dry, the leather will retain the mould

shape when it is removed from the mould. However removing the leather from

the mould requires knocking the mould out of the leather that has dried,

hardened, and shrunken/tightened around the mould.

NOTE: Because of the abuse from knocking

it out of the tightened leather, over time a mould begins to crack and

eventually falls apart, requiring a new mould to be made.

Because of the abuse that wood moulds

take, I have experimented with utilizing an epoxy resin to form my moulds.

The main reason for this is that the mould will last longer, thereby

delaying the need to produce more moulds. Secondarily, as I do not do

woodwork, it can be cheaper to produce an epoxy mould than have a wood mould

formed. To utilize the epoxy method, you have to make or find a shell in the

shape you want. A glass, ceramic or plastic container in the shape you want

can filled with epoxy, then broken away, once the resin has hardened. The

"Lost Wax" process can also be utilized to produce a mould. (Create the

mould in wax, surround it with Plaster of Paris, let the plaster harden,

melt away the wax, leaving an empty space in the shape desired, fill with

epoxy, let the epoxy harden, break away the plaster, and you have an epoxy

mould.)

NOTE: The use of the solid mould is the

procedure sources and records dating back to the Middle Ages cite. There are

a couple of alternative methods possible to shape the vessel, that will be

discussed later.

3. The next step is to create patterns

for the shapes the leather pieces need to be. The pattern consisted of three

parts: the body or shell, the plug, and the bottom. Refer to the attached

drawings to understand the shapes being sought. The attached drawings are of

the "standardized" type of jack being discussed and can be used as a

template. Merely enlarge the body-piece drawing until it is 8" (top to

bottom) in the middle. This will result in the dimensions for a quart jack,

and match up for use with the dimensions provided for the wooden mould.

Enlarge the handle or plug piece by the same amount. The bottom piece is

simply a circle of leather. For use with the "standardized" jack, it should

be 6" in diameter.

To create a pattern for a different size

or shape involves experimenting with folding cloth or paper templates until

achieving the shape/size sought after. The easiest method I have found is to

pin cloth around the mould, then trim it. Take the cloth off, lay on thin

cardboard or matte-board and draw around it. This forms the main section of

the shell piece, without handles. It should have a slight curve to

accommodate the forming of a rounded shape. You will now need to determine a

handle shape. I recommend using the handle shape provided in the attached

drawings, as this is the most period of shapes, but you can create your own.

If using the handle shape in the attached drawings to add to your own

pattern, merely enlarge it until its length is equal to the sides of your

body piece. Lay the enlargement next to the sides of the shell pieces, and

draw around it (on each side of the body piece) to complete the shell

pattern. The handle shape should also be drawn out on the cardboard, by

itself, as this forms the plug piece. The bottom piece should be a circle

whose diameter is about 2" larger than the bottom of the mould being used.

It is usually easier to form a pattern from an existing mould rather than

make a mould to fit an existing pattern, but it can be done. If you prefer

to attempt this method, you can use the attached patterns, enlarge them to

the size desired, then take measurements to form the

mould.

NOTE: Forming the pattern pieces to fit

your mould is perhaps the most difficult part of the

procedure.

4. Once you have the mould and pattern

pieces, you are ready to create your jack. The pattern pieces are laid on

the leather. Mark around the pieces and cut them out. The body or shell

piece is folded over so that the two handles overlap. Make sure that the

grain (smooth side) is on the outside. The plug piece is placed between the

two handles and all three are glued together, forming one thick handle.

Using pressure clamps, allow the cement to dry. Once the handle/plug section

dries, placement for the seam holes of the handle is determined. Mark,

groove and space the place for sewing holes by utilizing the groover and the

spacing wheel. The holes are then "punched" by hand, one at a time, with a

stabbing awl. As the holes are made they are sewn through (again by hand)

using the leathercrafter's two-needle stitch. Once the handle is sewn,

smooth out the edges with sandpaper.

5. The next step is to form the body

shape. This is done by soaking the shell piece in water until it is

thoroughly saturated with water and very flexible. Recommended time of

soaking is about 30 minutes. At this point the shell is stretched over the

mould and allowed to dry. Once dry, the mould is knocked out of the leather.

You will find that the leather will retain the shape of the mould and be

lighter in weight. [The reason for this is that by soaking the leather, the

natural oils in it come out into the water. This loss of oil lightens the

weight of the leather. The extraction of oil also re-aligns the fibers that

compose the leather making it harden, shrink slightly and causing it to

retain the shape it was last in.] Following the removal of the shell from

the mould, it is then trimmed at the top and bottom to form a level lip and

base to the vessel, and burnished (smoothed). Now it is ready to have a

bottom attached.

6. On the body piece, near the bottom,

seams for sewing the bottom piece in are determined, marked, grooved and

spaced in a manner similar to what was done on the handle. The bottom piece

is then soaked in water until flexible. It is then "stuffed" into the bottom

of the body piece, with the edge of the bottom piece bent back or curved

toward the bottom of the jack. With a stabbing awl, a hole is "punched" by

hand through the body piece and into the curled up edge of the bottom piece.

This hole is then sewn through. This procedure continues around the entire

jack until the bottom piece is completely sewn in. The bottom piece is then

trimmed off even with bottom of the body piece and burnished. Once the

bottom section is dry, it is time to coat the inside of the jack to make it

waterproof.

7. In period the jacks were lined with a

variety of substances. (Pitch, pine tar resin, beef/mutton fat tallow, or

beeswax.) Most, if not all, of these substances are considered today to be

hazardous or unhealthy, so they are not used. Until recently, most craftsmen

utilized a product known as Brewer's Pitch. It looked and acted like actual

pitch, but was actually a black thermoplastic that was safe, easy to use and

non-toxic. It was utilized by large beer manufacturers to line their wooden

beer vats. However, in the last few years, the beer companies switched from

lined wooden vats to massive plastic vats. Because of this, the company that

produced the Brewer's Pitch is no longer in business and it is not possible

to purchase more. Since this occurrence, most leathercraftsmen have been

experimenting with various epoxies and resins to find a suitable

replacement.

One of the most common linings used at

present are the non-toxic, food grade safe resins that are most notably used

on wooden toys for small children. One brand of this type of resin is

Envirotex. This resin is a two-part mixture that hardens after a period of

time.

To utilize the resin, I first tape the

seam between the bottom piece and the shell piece with masking tape. This

will help prevent any leaks that may result from the thin resin. I then

place a piece of waxed paper on the surface where I will set the jack once

lined. If some resin does leak through, this will not only protect the

surface, but prevent anything from sticking to the bottom of the jack. Next

I mix a batch of resin, pour it into the jack and "swish" it around until it

coats the inside. The jack is then set down in a normal position, and any

excess resin is allowed to pool in the bottom and harden there, affording

extra waterproofing there as that is the area most likely to leak. The

advantage of the resin over the former pitch is that it is easier to work

with. Brewer's Pitch required heating to a "molten" stage, required

protective gear for working with heated substances and smelled bad while it

was hot. The disadvantage of the resin is that it is a thinner liquid and

tries to leak out through any large seam holes rather than filling them,

which Brewer's Pitch would do. Also, the thinner, transparent resin does not

give the appearance of period pitch lining. However, in the interests of

health safety, this compromise must be made.

Another product that is available, is a

food-grade-safe resin that is called Brewer's Pitch by the company that

sells it, but it is actually a yellowish-colored modern pine tar substitute.

The major problem with this product is that it becoming tacky/sticky just

from holding it in your hand.

8. Once the lining has set and hardened,

the jack is tested for waterproofness. To do this, the jack is filled

completely to the top with water and let stand for 24 hours. If no leaks

appear, it is ready to be finished. If leaks do appear, the leather is

allowed to dry from the water and then a second coat of liner is applied.

This step is repeated until the jack proves to be waterproof.

9. The next step is to finish the

exterior of the jack. Conventional wisdom states that decoration on jacks is

not done until after it is formed, waterproofed and tested. The reason for

this is that the forming process stretches the leather, and if the design

were done before forming, it would be distorted by the forming process. The

jack is waterproofed and tested before decorating so that any spillage or

other problems do not ruin the decoration. However, experimentation has

shown that the carving of designs can be done on the shell piece, while it

is flat, before it is folded over and the handle sewn. The stretching is not

sufficient to distort the design. However, dyeing the leather or painting

the design must wait until this time, due to the soaking the leather goes

through.

NOTE: The most common design utilized in

period for jacks were coats-of-arms.

At this point, after the carving of the

design is done, the body of the jack is dyed with leather dye. If desired,

the design is then painted. The paint I recommend to use is modern acrylic

paint. There are several reasons for the use of this type of paint. It is

easy to obtain, it provides a good heraldic color, it will retain it's color

for a much longer period of time than period-type paints and it works well

on leather.

10. The last step is to coat the outside

with a clear lacquer, a process that was many times done in

period.

VII. Alternate Formation

Methods

A. Two-step moulding. Instead of a solid

mould, this procedure uses branches or round wood pieces of different sizes.

The small circumference end of the leather shell is soaked and formed on an

appropriate size piece of wood. Once it has dried, the other (larger) end is

soaked and formed over a second larger piece of wood. You allow the leather to

"naturally" form the bell shape by stretching from the small size to the large

size. The disadvantage is that it takes longer and there is a little less

uniformity in shape when making several. The advantage is that you don't have

to make a pattern to fit your mould. You can use the standard pattern provided

in the attached drawings, enlarge them to the size of the jack you want, then

form the round pieces to fit the size of the leather.

B. Sand forming. This involves sewing the

shell piece, then precisely marking the bottom piece, soaking it and sewing it

in before the shell is formed. I would recommend drawing circles in the

appropriate size on the bottom piece, before soaking. Then when sewing, make

sure that your stitches come back through the circle. This will help guarantee

that you are forming a perfect circle for the bottom. Once the bottom is sewn

in, the entire piece is soaked. Once soaked the vessel is filled with fine

sand. Use a thick rod or stick to "firmly pack the sand in" and to stretch the

leather into the desired shape. Keep adding sand until the vessel is filled.

Some hand forming of the shape may be necessary. Once totally full, allow the

shell to dry. This should form the completed blank shell. Now proceed with the

rest of the steps as usual. The disadvantages to this method are that it

requires precision sewing of the bottom piece, to form a round shaped bottom.

Also, it can be difficult to get the leather to stretch consistently to create

an evenly formed vessel. The advantage is that you don't have to make a

pattern to fit a mould. You can use the standard pattern provided in the

attached drawings, enlarge them to the size of the jack you want, then use the

sand to make the final shape.

VIII.

Bibliography

Black Jacks and Leather Bottells

by

Oliver Baker

Compleat Anachronist #8

by Trobere

Oakseed

Compleat Anachronist #18

by Trobere

Oakseed

Inns, Ales and Drinking Customs of Old

England

by Frederick W. Hackwood

Leathercraftsmanship

by John W.

Waterer

©1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004,

2005, 2006, 2007 Ron Knight

Baron Modar Neznanich, Order of the Pelican

e-mail: modar@everestkc.net

Permission to Print

To SCA Interests

Page

To New Member

Information

To Modar's Heraldry

Page

Back to Modar's

Leatherwork Page

Modar the Black Pelican